You just got a great bakelite radio, or jewelry or even poker chips. But is it REALLY Bakelite? Many retailers either try to fool customers or really can't tell the difference themselves between several types of vintage plastics. Let's see if we can help!

Bakelite

Dr. Leo Baekeland and his team of chemists developed phenol formaldehyde in the early 1900s. Baekeland then began experimenting on strengthening wood by impregnating it with a synthetic resin, rather than coating it. By controlling the pressure and temperature applied to phenol and formaldehyde, Baekeland produced a hard moldable material that he named "Bakelite", after himself. It was the first synthetic thermosetting plastic produced, and Baekeland speculated on "the thousand and one ... articles" it could be used to make.

The applications for this plastic were indeed vast, according to the American Chemical Society:

"Bakelite can be molded, and in this regard was better than celluloid and also less expensive to make. Moreover, it could be molded very quickly, an enormous advantage in mass production processes where many identical units were produced one after the other. Bakelite is a thermosetting resin—that is, once molded, it retains its shape even if heated or subjected to various solvents."

Celluloid was also very flammable giving Bakelite another advantage. It could be used in situations where high heat was of concern without issue, but it wasn't very attractive or versatile for use in consumer products when it came to color.

Bakelite was made from 1907-27. Bakelite used fillers of cloth, paper, cotton and even sometimes asbestos. This meant the plastic was heavy, very strong, opaque and came in only dark colors. Bakelite usually came in only black and dark brown, and was used mostly for ‘utilitarian’ purposes, including pipe fittings, coffee pot handles, pistol grips and electrical outlets.

Catalin

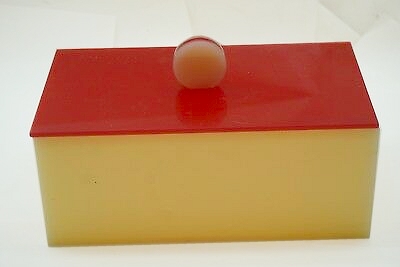

When Bakelite’s patent ran out in 1927, the process was picked up by the American Catalin Company, which called their version of the plastic Catalin. The American Catalin Company used the same phenol formaldehyde chemicals, but made the plastic in a different way. In particular no fillers were used. This meant that, unlike the dark and dreary Bakelite, catalin was often translucenct and made in a wide variety of bright colors and interesting designs, including a marble of different colors

Catalin was used for more fun, decorative and collectible items, including jewelry, toys, trinkets, decorated boxes, brightly colored radios. Catalin tended to shrink with age, which explains for the sometimes warped and shunken frames for catalin radios. Catalin was made from 1928 to about World War II.

So while Bakelite was used for items like insulators for electrical systems or handles on Deco-era toasters, for instance, Catalin was used for manufacturing varied jewelry, colorful radios, and other consumer goods widely collected today. Even so, the majority of these objects are described as Bakelite now. You may occasionally see sellers use both terms when marketing plastics of this nature as well.

Celluloid

Celluloid was one of the first plastics to be widely used in making jewelry. Celluloid was originally developed in England in the 1850s but first commercialized in 1868 by John Wesley Hyatt, whose company eventually became the American Celluloid and Chemical Manufacturing Company-- subsequently the Celanese Corporation.

Celluloid was one of the first plastics to be widely used in making jewelry. Celluloid was originally developed in England in the 1850s but first commercialized in 1868 by John Wesley Hyatt, whose company eventually became the American Celluloid and Chemical Manufacturing Company-- subsequently the Celanese Corporation.

Jewelry made of celluloid dates to about 1900 and was quite popular during the Art Deco period. Celluloid has characteristics which are different from other plastics. Celluloid items tend to be thinner and lighter than Bakelite, and it is definitely more brittle and can crack when heated to higher temperatures.

Some celluloid pieces can even be flammable, and while more brittle than Bakelite it can still be bent or twisted. Under hot water, most celluloid has a smell like vinegar or old camphor. Celluloid jewelry can be damaged by moisture, temperature extremes, or chemicals. Celluloid that has been stored in a closed environment for long periods can also dull quite dramatically and even crack.

Lucite

Lucite

Lucite is a resin created by DuPont in 1937. DuPont widely licensed Lucite for use in jewelry because it was inexpensive and easy to work with in carving, inlays, etc. Like Bakelite, Lucite could be manufactured in most any color and can run from opaque to transparent. Lucite was particularly popular from about 1940 to 1953, but it is still produced and widely used today. Embedded Lucite made during this period by incorporating glitter, rhinestones, sea shells, and other materials was widely used in hard sided purses which are actively collected today.

How to identify Bakelite & Catalin from other plastics

- Smell it. Bakelite and Catalin will have a distinctive formaldehyde odor when rubbed until warm or run under hot water, this is a good indication that it's bakelite.

Lucite, a plastic that can resemble bakelite/catalin has no smell under the hot water/rub test. ‘French bakelite,’ which is a mostly modern faux-bakelite, smells like burnt or sour milk. - Listen to it: You can hear a "clunk" sound when banging two pieces of bakelite together. You will notice the difference from banging two pieces of plastic together.

- Feel it: Bakelite is heavier than modern plastic and will feel more substantial in your hand than a plastic piece of similar size.

- Simichrome it: One preferred method by collectors for testing is using Simichrome polish. Gently rub a small spot on the inside or back of the item being tested with a soft cloth. If it is Bakelite, the cloth should turn yellow with ease (although the color may vary from light to dark). Bakelite testing pads are also an alternative to carrying a tube of Simichrome polish with you when you shop. These easy-to-stow pads provide a similar result to Simichrome

- 409 it: Like the Simichrome polish, you can test a piece with a cotton swab covered in Formula 409 cleaner. Test on the inside or back of a piece to get a yellowish color. If the piece is lacquered, it may have a false positive.

- Inspect it: Look for wear like scratches and patina that new pieces of plastic would not normally exhibit. Also, look for tiny chips on the edges of carvings. Examine the piece with a jeweler's loupe or another type of magnifier, if needed. Generally, old pieces of bakelite will have signs of wear. Also note, bakelite pieces will not have seam marks like molded plastic pieces.

Celluloid is older (mid 1800s to early 1900s), so an older piece will be celluloid rather than bakelite or catalin. Also, celluloid was often used to mimic ivory, such as in brush handles, dice and toys. It's very thin and can often be translucent when held up to the light. You can also rub or run hot water over celluloid to smell it. Celluloid will have a camphor smell when warm.

Lucite has a slick feel and is fairly light weight. It is lighter in weight than Catalin. It can be dyed any color and may resemble catalin. If you put Lucite under hot water or rub it vigorously, it has no smell. The most common way to identify vintage (versus modern) Lucite is by the style. Vintage styles include marble and granite-style Lucite (has a distinct marble or granite multi-coloring), clear Lucite with objects embedded in it (such as plants, bugs, trinkets), confetti Lucite which is clear Lucite with glitter inside objects inside, and moonglow which seems to glow under light.

Lucite has a slick feel and is fairly light weight. It is lighter in weight than Catalin. It can be dyed any color and may resemble catalin. If you put Lucite under hot water or rub it vigorously, it has no smell. The most common way to identify vintage (versus modern) Lucite is by the style. Vintage styles include marble and granite-style Lucite (has a distinct marble or granite multi-coloring), clear Lucite with objects embedded in it (such as plants, bugs, trinkets), confetti Lucite which is clear Lucite with glitter inside objects inside, and moonglow which seems to glow under light.

So is it Bakelite or Catalin?

If you can determined an item is phenol formaldehyde with one of the above tests, the next question is: "Is it bakelite or catalin?"

If you know the date of the item, then it’s easy. Bakelite: 1907-1927. Catalin: 1928-1940s.

Bakelite only comes in dark colors, usually black or dark brown/maroonish. Catalin can come in a wide variety of colors, including bright colors and marbling.

Bakelite is opaque, while catalin is often translucent (can often see this at the edges of an item). If the item is brightly colored jewelry or similar items, it is more than likely catalin.

{gallery}blog/bakelite,turbo = 1,Show image name=1{/gallery}